Plein Air – join the club!

We’ve noticed Plein Air Competitions springing up all over the place of late – it seems painting outdoors is growing in popularity and we couldn’t be happier! This resurgence in plein air could be attributed to the pandemic, which saw a greater number of artists venturing outside to paint, rather than sticking to their usual studio-based routine. People in general are seeking communities more than ever, as a respite from isolating environments or working from home. This could include wild swimming clubs, running clubs, walking groups and painting groups.

We know that being outdoors has so many health benefits and it’s a welcome challenge for most artists. It harks back to a more simplistic – or should we say purist? – approach to life, rather than being stuck to a screen 24 hours a day. Painting outdoors requires your complete focus, overcoming both practical and physical challenges. We asked oil painter Georgina Potter for her top tips, ‘if you’re serious about painting plein air, you need to get out in all weathers. I always stand on cardboard to keep the cold at bay.’ Read the full article here.

Pegasus Art Plein Air

This year alone, we are sponsoring Stroud Plein Air, Wimborne Plein Air (both brand new in 2024) and Broadway Paint Off. As advocates of this historic genre, we like to show our support for plein-air events which encourage painting, connection and a love of nature. We also run our own Plein Air Workshops in nearby Painswick and on the Stroudwater Canal which runs alongside Griffin Mill.

20th April – Capturing Reality with Tom Hughes

29th June – Greens without Green with Barry Herniman

27th & 28th July – Painswick Plein Air with Roger Dellar

John Constable pioneered a plein-air approach to painting in the early 19th century, then from 1860 onwards it became fundamental to the Impressionist movement which brought this genre into the mainstream. Similarly, the Hudson River School in the United States grew in stature and the Luminists almost deified Mother Nature – her forests, mountains and wildlife. Before this time, it would have been unthinkable that paintings sketched outdoors were nothing more than preparatory studies. Developments in art materials, the advent of paint becoming available in tubes or pans (paint cakes) around the 1870’s, plus portable easels that were more lightweight than their earlier counterparts, suddenly made it a possibility to paint outside. Before this, artists made their paints by grinding pigments with oils – it was a messy business! Read our blog ‘What is it about Watercolour?’ to track the development of this medium.

The Golden Age of Watercolour

‘The Golden Age of Watercolour’ from the mid 18th to mid 19th centuries was an explosion of interest by amateurs who started to take up the activity as a hobby. Watercolours provided the ideal medium, lightweight and minimal – among the aristocratic classes, painting was considered an important adornment of a ‘proper’ education.

En plein air carrying cases, or pochades, are described as early as 1731 as ‘constructed of mahogany and fitted with brass hardware and embossed-leather linings, providing porcelain mixing pans, wash bowls, storage tins for chalks or charcoals, trays for brushes and porte-crayons, scrapers, blocks of ink and colours.’

Winsor & Newton

William Reeves, an 18th-century colour man, was awarded the Silver Palette of the Society of Arts for his invention of the ‘paint cake’ in 1781. These small, hard cakes of soluble watercolour were revolutionary. By the 1830s artists could buy watercolours in porcelain pans, before further advancements in 1842 produced the first watercolours in collapsible metal tubes, thanks to Winsor & Newton. Their machine ground pigments produced consistently high-quality pigments which set an international standard and they were granted a Royal Warrant in 1841. Before long, artists could liberally wash their paper with vivid colours never used before in this way – early critics were proved very wrong indeed!

How the Shilling Colour Box helped the plein air movement

William Winsor and Henry Newton were already working alongside some of London’s well-known colour men who procured rare pigments from across the globe and assembled in the artist’s quarter around Rathbone Place, central London. Indeed Constable, a neighbour, was one of their early customers. Not all colour-men were as scrupulous as Winsor & Newton however and would sell unstable mixes that would discolour or react unfavourably with other pigments. New compounds that were suddenly affordable, such as cerulean, chrome orange and cadmium yellow minimised time spent grinding and mixing with a pestle and mortar in the studio! The pocket-sized ‘Shilling Colour Box’ – a lightweight japanned tin with pan colours and mixing palettes became a Victorian best-seller, selling more than eleven million units between 1853 and 1870. The dye was cast, and watercolour ….. and plein air…. has remained fashionable ever since.

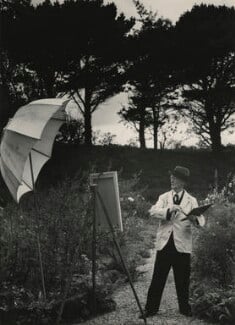

The rural naturalists took this style of painting as an important technical approach to naturalism. The Newlyn School was a major proponent of the technique in the later 19th century. Here is a picture of Stanhope Forbes who painted in extreme conditions, often tying down his easel with guide ropes on the beaches around Newlyn where he would paint.

David Hockney, the grandfather of modern plein air painting, exhibited his Grand Canyon works in the 90’s and the famous Yorkshire landscapes in the 2000’s made with his iPad. The 288 foot long frieze is on view at Musee de l’Orangerie in Paris, celebrating the changing seasons in Normandy, where he spent lockdown painting.

What the artists say

We spoke to our regular, visiting painting tutor David DJ Johnson about his fascination with plein air;

“Being outside in nature is a huge source of inspiration for me, and if you are patient and look with the right kind of eyes, there is so much to see. When you paint outside it is easier to experience true colours, light and tonal values in the landscape. I capture the values in oil paint and take photographs that I can work from later on. Back in my studio I will use the oil sketch as a reference for colour and light and the photo will help me with composition and perspective, helping me to produce a larger painting. I find when I’m outside I can get ‘in the zone’ and become totally focused.

Extreme Plein Air

It was a friend who suggested that I was an ‘extreme en plein air’ painter because I was climbing high up into the mountains to paint. Mountaineering and rock climbing have been a lifelong passion for me, so combining the two was a natural progression. My experience of climbing helps me to stay safe in extreme conditions while I am trying to capture the landscape onto canvas from lofty viewpoints!

“Painting outdoors has always been an intensely joyful experience. But now there is this layer that makes it feel as though I’m there seeking medicine.” Jeremy Miranda

“Reality is so much more interesting than fictional painting in a studio,” Cabeza de Baca

“Hell yeah, I am a plein air cat, I’ve been doing it always, seriously since around 2006. Love the performative quality of it. Anselm Kiefer says there is no innocent landscape—and he is probably right. This plein air urge—it is almost the artist under the other artist who always wants to break free, the artist who just wants to go out in the weather and paint what there is. I love that approach. I’d forgotten how exciting and intuitive that was. For me, painting from life is incredibly freeing.” Ragnar Kjartansson